The Truth about Comedogenic Ingredients and Acne Prone Skin

There is so much misinformation about comedogenic ingredients out there and I know acne-prone are very concerned about it, so I wanted to shed some light on the topic.

There are a few key things that you should know about this misleading word.

Defining “Comedogenic”

It’s easy to define in theory but hard to pin down in practice.

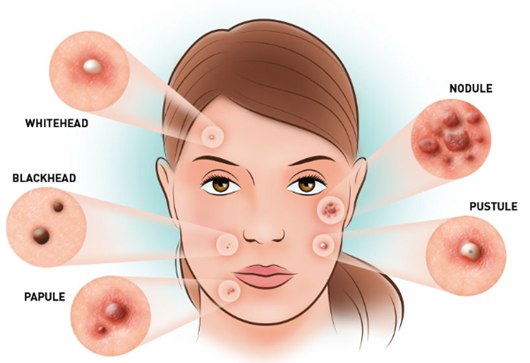

A comedogenic ingredient means that it clogs pores. This doesn’t always happen quickly, and it can take months of using a comedogenic product before clogging is noticeable. Also, very important and this is where the problem comes in: individual skin chemistry can determine the extent of an ingredient’s comedogenicity, so it is highly variable between people.

Some things that complicate the idea of “comedogenic” drastically:

With a “comedogenic” ingredient or formula, one person may have no reaction, while another may have excessively clogged pores in a few weeks. Some people are just more sensitive to certain ingredients and react differently, for various reasons. In acne-prone skins, this is also true. Some may break out with algae extract for example, but others do fine.

Even ingredients that are not typically comedogenic can become so by a person’s own unique skin chemistry.

Human sebum is naturally somewhat comedogenic (especially in the case of acne-prone skin, which often presents with abnormally sticky sebum), so even if clients who are prone to clogging avoid all likely comedogenic products, they are not necessarily guaranteed protection against comedos.

There is NO definitive way to test for comedogenicity. The test that is most often referred to is the rabbit’s ear test, where ingredients were applied to the inner ear of rabbits, and follicular keratosis (the process which comedogenic ingredients increase and which causes pore clogging) was analysed both visually and microscopically after a few weeks.

The question remains whether a rabbit’s ear is a good proxy for all types of acne-prone skins, and it probably isn’t.

Despite all the lists you find on the internet, the truth is, there is no DEFINITIVE list of comedogenic ingredients. You can see this in the discrepancies between the lists. Some have ingredients others don’t, and the same ingredient can have variable comedogenic ratings depending on which list you refer to.

Here’s the big kicker though – formulations matter a lot. A formula is not just a sum of its parts—ingredient combinations can turn a comedogenic ingredient into a noncomedogenic ingredient and vice versa. The same thing goes for ingredient percentage – a comedogenic ingredient included at a smaller percentage can easily become harmless and non-comedogenic. Of course, depending upon the ingredient, the concentration of that ingredient within the formula is more important for some ingredients than others. I will offer case studies below.

Also, the method in which an ingredient is extracted and processed plays a role. Whether an ingredient was refined (and how, since there are different methods to refining), hydrogenated (quick definition: Chemically combining an unsaturated compound with hydrogen. Liquid vegetable oils are often hydrogenated to turn them into solids) or fractionated (removing or altering the percentage of chemical components of a material through heat or hydrolysis) can dramatically change its comedogenicity ranking. Some case studies will be included below to give concrete examples. The source and the quality and purity of the raw material can also affect its rating. The concerns here are especially valid for natural oils and butter. Obviously, these variables cannot be easily determined by reading an ingredient list.

In the words of Albert Kligman, pioneer of the comedogenicity scale:

“One cannot determine from a reading of the ingredients whether a given product will be acnegenic or not. What matters solely is the behaviour of the product itself.” – Kligman, 1996

So even the inventor of the comedogenicity scale has flat-out said that it shouldn’t be used to screen ingredients lists!

Comedogenicity is totally unregulated. The authorities do define a comedogenic ingredient as one that is known to clog pores. However, they do not define a list of ingredients that need to be excluded for a product to use the term “noncomedogenic.” Therefore, any company can make the claim that its product is noncomedogenic and still comply with the guidelines. In addition, no standardized testing and no watchdog groups exist to catch misuse of the claim.

What’s wrong with the comedogenicity scale?

The problem is that the studies that produced the comedogenicity ratings don’t reflect real-world usage, for a number of reasons:

TESTS AREN’T DONE IN REAL-WORLD CONDITIONS

In an ideal world, we’d test every single product on every single person’s face, and develop a definitive comedogenicity rating list based on that. But this would be impossible – it would cost too much, there are too many products, and getting a lot of people to only use the one product and not change their daily routine for weeks or months at a time would be a mammoth task.

THE MOST COMMON RABBIT EAR TEST IS FLAWED

The most common test for comedogenicity is the rabbit ear test, pioneered in cosmetics testing by two famous dermatologists, Albert Kligman and James Fulton, in the 1970s. This involves applying a substance to the inner ear of a rabbit and waiting a few weeks to see if any clogged pores formed. Because rabbit ears are more sensitive than human skin, they reacted to comedogenic products faster, which was more convenient.

Unfortunately, this also meant that there were lots of false positives, where ingredients that are non-comedogenic in humans would be found to be comedogenic in the hypersensitive rabbit model. Additionally, in the original tests, the scientists didn’t realise that there are naturally enlarged pores in rabbit ears. Some results counted these as acne, leading to even more false positives.

The most famous false positive is petroleum jelly (petrolatum or Vaseline, which was corrected in the late 1980s, but this was debated until the mid-1990s – that’s why the myth that Vaseline and oily products cause pimples is still so pervasive.

This wasn’t the first time the rabbit ear tests were questioned – conflicting results were commonplace, and comedogenicity lists frequently disagreed with each other (and still do).

More recently in 2007, dermatologists Mirshahpanah and Maibach went so far as to say:

“[the rabbit ear] model is unable to accurately depict the acnegenic potential of chemical compounds, and is therefore only valuable for distinguishing absolute negatives.” – Mirshahpanah and Maibach, 2007

TESTS ON HUMAN SUBJECTS ARE ALSO FLAWED

If rabbit ears don’t reflect what happens on human skin, then the obvious solution is to test on humans, right? Yes…but there are problems there too!

Skin from the subject’s back is usually used. Back skin is very different from facial skin – for example, facial skin has a lot more hair follicles, and it’s exposed to much more sunlight. Whether they’ll react the same way to products is questionable.

Human tests also use people with large pores who are prone to getting pimples. Will someone with small pores necessarily react the same way? What about people with medium sized pores?

The ingredients to be tested are swabbed on and occluded by covering with a bandage after application, which is not what you’d typically do with your skincare products.

The tests were done on relatively small samples (typically less than 10 subjects).

So again, the usefulness of the results of these tests – whether we can apply these ratings in our everyday usage of skin care products and cosmetics – has been overstated.